Research, ux design, product design, branding. prototypingDesigning a companion for invisible disabilities

Role: Lead Product Designer & Researcher (Self-Initiated)

Outcome: Validated a human-centered, non-clinical approach to health management through rigorous user testing.

The ProblemHealth apps felt like homework, not help. Existing tools for managing anxiety, depression, and chronic pain were designed by clinicians for data collection—sterile, cold, and demanding.

The Friction: Users were overwhelmed by "medicalized" interfaces that required detailed data entry during their worst moments.

The Risk: The cognitive load of tracking symptoms often led to abandonment, leaving users without support when they needed it most.

The Reality: Invisible disabilities are exhausting to explain. Users needed a way to signal their status to support systems without constant justification.

The StrategyHumanize the tracking experience. I moved away from the "patient" model to a "companion" model—building a tool that felt like a friend rather than a medical chart.

Low-Barrier Entry: Replaced detailed journaling with one-tap emoji check-ins and quick-log interactions.

Communication as Infrastructure: Built "SOS" features that allowed users to alert trusted contacts without having to articulate their distress.

Calm UI: A soft, muted visual language that reduced anxiety rather than inducing it with "alert" colors.

Community app design / Social platform UX / Mobile community featuresCore Problems

1. Existing health apps felt clinical

They were designed by medical professionals for medical professionals. Sterile interfaces. Medical jargon. Zero personality. Using them felt like homework.

2. Invisible disabilities are, well, invisible

People couldn't see my struggle. I looked "fine." But fine was exhausting to maintain. I needed a way to communicate my needs without constant explanation.

3. Managing multiple conditions is overwhelming

Prescriptions, symptoms, triggers, appointments, emergency contacts—it's a lot. Existing apps either did one thing (badly) or tried to do everything (and failed at all of it).

4. Stigma makes everything harder

Talking about mental health and chronic pain comes with judgment. I needed something that normalized these experiences and made asking for help feel less scary.

5. One-size-fits-all doesn't work

My anxiety looks different from your anxiety. My coping mechanisms aren't universal. Apps that assumed everyone's experience was identical felt alienating.

The Process

-

The Research Question:

Was this just a "me" problem, or would this resonate with others?I wasn't looking to build something just for me. I needed to know if other people with invisible disabilities faced similar challenges—and whether an app like this would actually help.

Recruitment Strategy:

I cast a wide net, recruiting participants through:Facebook ads targeting mental health and chronic illness communities

Local bookstores (community bulletin boards, asking staff to share)

The informal "smokers lounge" outside my college (best impromptu research location, honestly)

Participant Criteria:

Willing to disclose they have a formal diagnosis related to mental health or an invisible illness

NOT required to disclose the specific diagnosis (privacy and comfort first)

The Reality Check:

I aimed for 10 participants. I got 9. (Shoutout to the last-minute cancellation who haunts every researcher's dreams.)Interview Format:

Semi-structured interviews, 30-45 minutes each

Conducted over two weeks

Mix of in-person and phone conversations

Questions focused on daily management, pain points, and coping strategies

-

Emergency support: One-tap SOS messages to trusted contacts

Pattern recognition: Visualizing trends without overwhelming users

Community features: Safe spaces for connection without forced vulnerability

The "Test With Literally Anyone" Phase:

Since I was exploring interaction patterns, I didn't need people with invisible disabilities to test basic usability. I needed humans.

I tested paper prototypes and early Sketch mockups with:

Classmates between design critiques

Friends over coffee

My roommate who reluctantly became my unofficial UX consultant

The barista who made my anxiety-inducing amount of coffee

Random people at the library who were willing to humor me

What I tested:

Can people understand the iconography?

Is the navigation intuitive?

Does the medication logging feel fast?

Are the emergency contact features easy to find?

What I learned:

People got confused by too many options on one screen (simplified navigation)

Iconography needed labels until patterns were learned (added tooltips)

Users wanted more visual feedback (added micro-interactions and confirmations)

Emergency features needed to be obvious but not alarming (refined visual hierarchy)

This iterative process slowly informed the visual language: calm, soft, approachable. Not clinical white. Not aggressive red. Something that felt like a gentle companion, not a medical device.

-

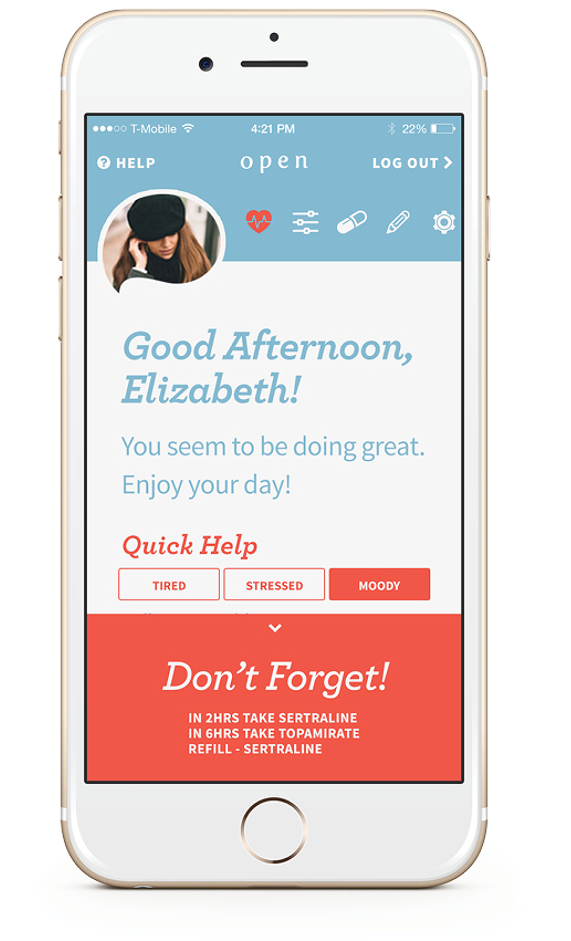

Color Palette:

Soft, muted tones. Calming but not infantilizing. I avoided harsh whites (too clinical) and aggressive reds (too alarming). Instead: soft blues, warm neutrals, gentle greens.Typography:

Readable. Sans-serif. Nothing too stylized or hard to parse when you're already overwhelmed.Iconography:

Simple, friendly, not too abstract. Every icon had a label until users learned the pattern. Clarity over cleverness.Micro-interactions:

Subtle animations. Gentle confirmations. Visual feedback that said "we see you, we've got this" without being distracting.Tone:

Encouraging, not preachy. Supportive, not condescending. Human, not robotic.

“I tried journaling my mood every day. It lasted three days. I felt like I was failing at tracking my failures.”

““People just assume I’m being lazy or flaky. They can’t see that getting out of bed took everything I had today.””

“I freeze in therapy appointments. I forget what I wanted to say. I leave feeling like I wasted the session.”

Research

What I Learned: Key Insights from 9 Interviews

Insight 1: The "invisible" part is the hardest part

Finding: 6 out of 9 participants described feeling misunderstood or judged because their conditions weren't visible. They wanted a way to communicate their needs without constant justification.

Design implication: Create tools that help users signal their status to support systems—without oversharing or making it dramatic.

Insight 2: Medication management is surprisingly complex

Finding: 7 out of 9 participants struggled with medication tracking. Existing apps were too complicated or sent annoying notifications they'd eventually ignore.

Design implication: Simple medication logging with gentle reminders—not aggressive, shame-inducing alarms.

Insight 3: Symptom tracking feels like homework

Finding: Most participants wanted to track symptoms but found existing methods either too clinical (rate your pain 1-10) or too open-ended (what do I even write?).

Design implication: Make symptom logging stupid easy. Quick taps, not essays. Patterns revealed over time, not judgment in the moment.

Insight 4: Bad days need immediate support—not a schedule

"When I'm spiraling, I don't need a meditation app. I need my best friend to know I'm not okay without me having to explain it."

— Participant 5

Finding: 5 out of 9 participants described needing immediate support during acute episodes—but reaching out felt impossible in the moment.

Design implication: Pre-configured "I need help" messages that can be sent with one tap to trusted contacts. Remove the barrier of having to articulate distress when you're already distressed.

Insight 5: Triggers are unique, but patterns are universal

Finding: Everyone's triggers were different, but the need to identify and anticipate them was universal.

Design implication: Customizable trigger tracking with pattern recognition. Help users see their trends without prescribing what "should" trigger them.

Insight 6: Talking to professionals is hard

Finding: Participants struggled to communicate their experiences to therapists, doctors, and support systems—especially in the moment.

Design implication: Tools to prepare for appointments: symptom summaries, patterns over time, pre-written talking points. Give users language when words fail.

The Solution: What Open Became

Core Features:

1. Medication Management

Quick-log prescriptions with one tap

Gentle reminders (not aggressive alarms)

Refill tracking

Side effect logging

2. Symptom & Mood Tracking

Fast check-ins (emoji-based mood, pain level, energy)

Optional detailed journaling

Pattern visualization over time

Trigger identification

3. Emergency Support System

Pre-configured "I need help" messages

One-tap contact to trusted support people

Crisis resources (hotlines, grounding techniques)

No judgment, just immediate access

4. Professional Communication Tools

Appointment prep summaries

Symptom history exports for doctors

Pre-written talking points for therapy

Progress tracking

Testing the Final Prototype

Methodology:

For the final round of testing, I went back to participants with invisible disabilities. I wanted to validate that the solution actually resonated with the people it was designed for.

Format:

6 participants (mix of original interviewees and new recruits)

30-minute sessions with interactive Sketch prototype

Tasks: Log medication, track mood, send emergency message, prepare for appointment

Think-aloud protocol

Post-test interview about emotional response and usefulness

The Response: Quotes from Final Testing

"This is the first health app that doesn't make me feel like a patient. It feels like a friend."

— Final test participant 2

"The emergency contact feature—I wish I had this last week. I was having a panic attack and couldn't text. This would've helped."

— Final test participant 4

"I love that I don't have to write paragraphs. Just tap and move on. That's all I have energy for some days."

— Final test participant 1

"The color palette feels calm. I didn't realize how much clinical white stresses me out until I saw this."

— Final test participant 5

"Can you build this? Like, actually build this? Because I would pay for this."

— Final test participant 3

"It doesn't feel like it's judging me. That matters more than I can explain."

— Final test participant 6

Outcomes & Impact

The Reality:

The app was never developed. This was a personal project, a thesis exploration, a design exercise born from lived experience.

But: The overwhelming positivity from testing validated something important: there's a real need for health tools that feel human.

People with invisible disabilities don't need more clinical apps. They need companions. They need tools that respect their energy levels, their privacy, their humanity.

What This Project Gave Me:

1. Validation that design can solve personal problems

I wasn't just designing for empathy—I was designing from empathy. And that made it better.

2. Practice in user-centered research

Recruiting participants, conducting interviews, synthesizing insights—this project built skills I still use today.

3. A portfolio piece that tells a story

Not every project needs to ship to be meaningful. This project showed I could identify a problem, research it, and design a thoughtful solution. It reminded me why I do this.

4. Proof that accessibility and inclusive design matter

Designing for invisible disabilities taught me to design for constraints, edge cases, and human variability. It made me a better designer for everything else.